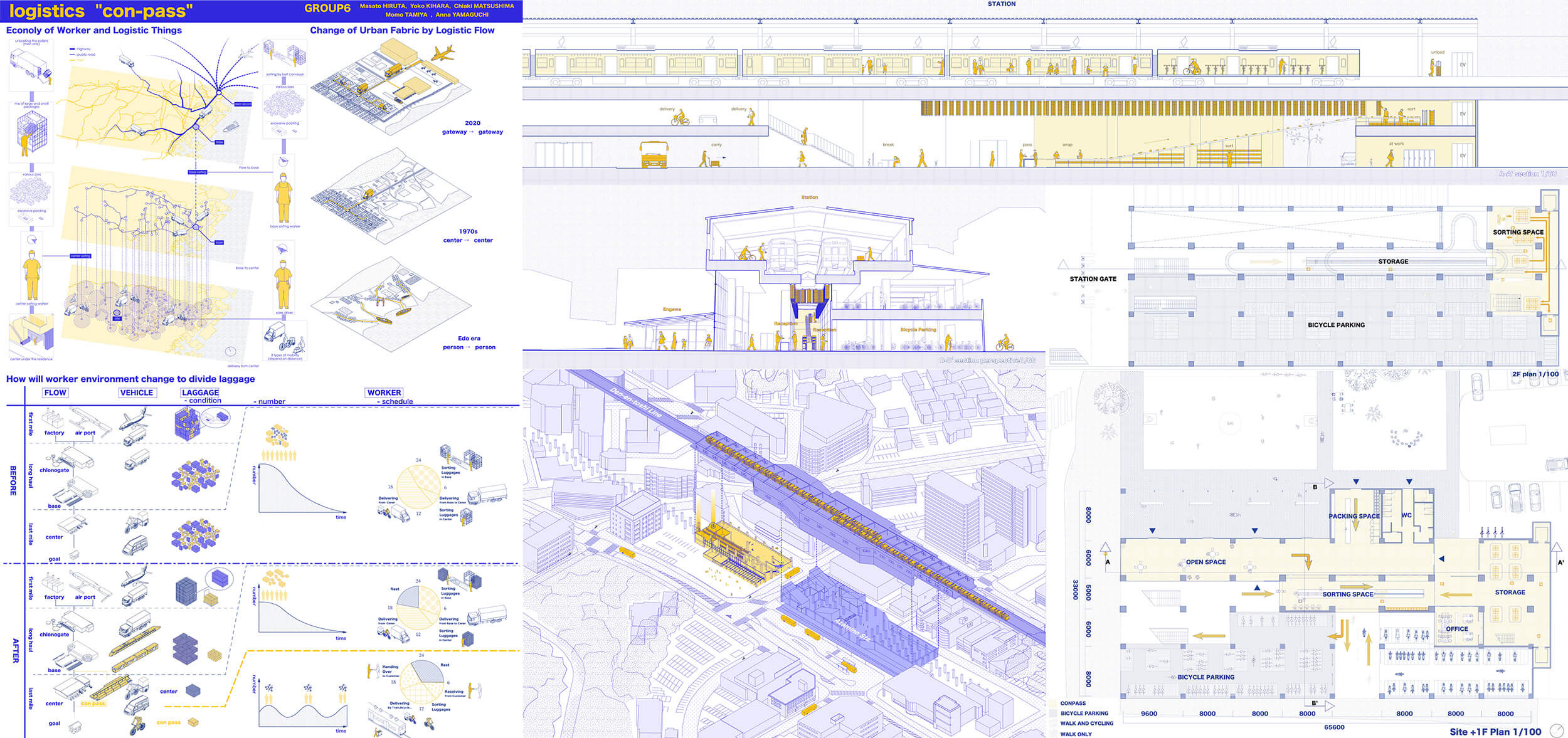

While highly efficient logistic systems have been established in recent years, the last mile is still carried by human hands. Now that the volume of packages is increasing due to the impact of COVID-19, it is necessary to rethink the working place of essential workers in logistics.

Our proposal is a transportation system for small packages that utilize the existing train network. By utilizing the existing infrastructure and involving local users in the first and last mile, the burden on Essential Workers will be distributed.

In logistics, where more and more packages are being shipped, utilizing existing stock will become more important than building huge warehouses.

We hope this video will give you an opportunity to look back on the current situation around the essential workers.

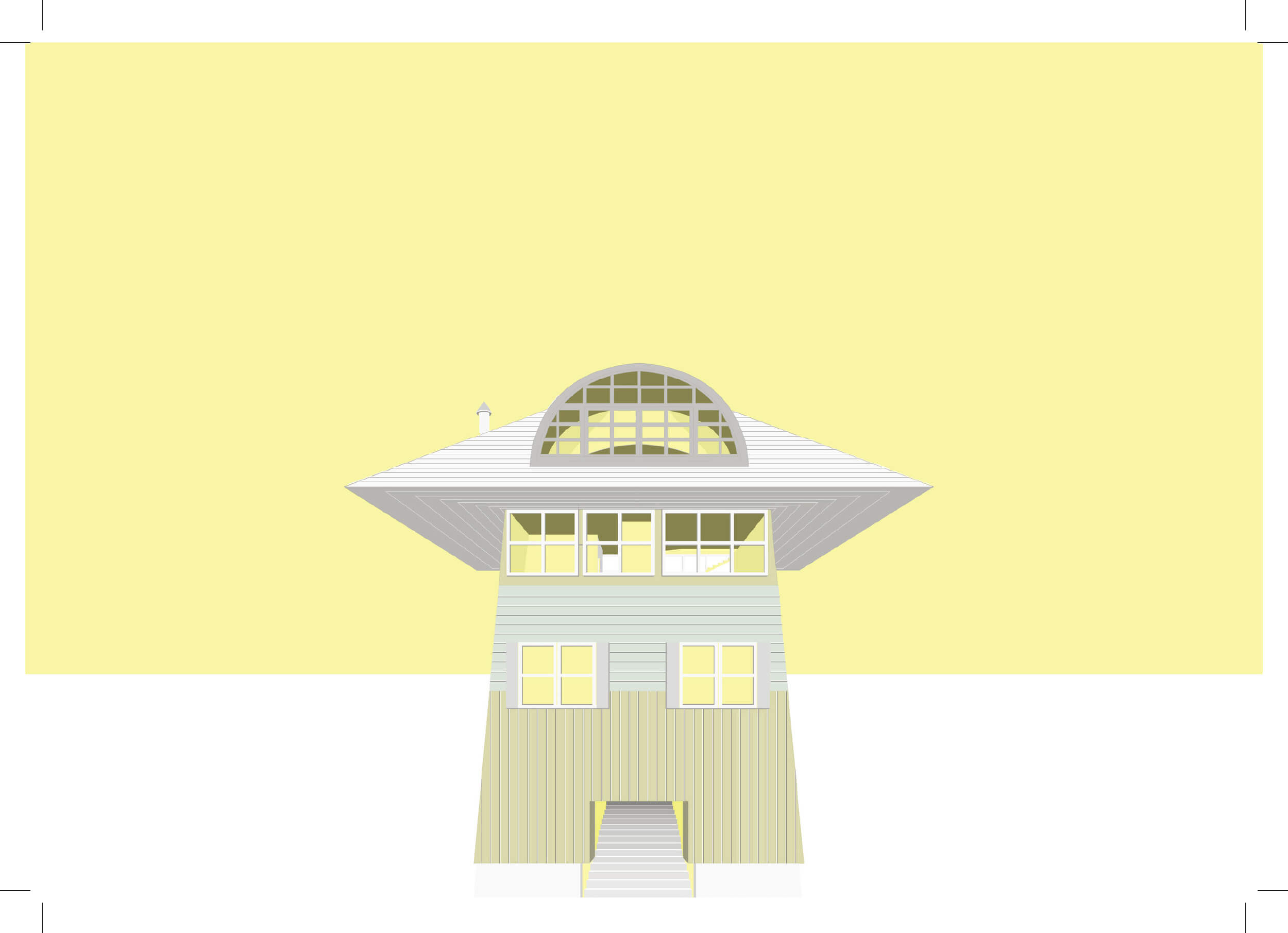

House in Vail

The House in Vail, CO, is proof that complexity and contradiction lead to ambiguity and richness of meaning. It consists of two different sorts of verticality: one articulated via the site context, the other contained by a sheer surface. North and south elevations are totally different, and the perception of the house from outside and inside is likewise contradictory. The scale of the roof and façade elements contributes to perceptual ambiguity- the real height is never directly revealed. Inside, depending on the height at which the observer is positioned, the house is perceived as either a tower or a small studio. By playing on this characteristic, while keeping the Tokyo context in mind, our new proposal suggests a building, divided into two parts, with mixed functions linked by an out of scale stair and a bridge that also inflates the perceived scale.

From the road, the entry is ambiguous, for there is no door in the main façade. Instead, it is located at the back. On the front left-hand side, a big stair emerges and continues along the whole site, as well as inside the building. It is the connection between the single parts of the house and its more unified surface that make it a whole. The outside is a semi-public space. Also, the way in which each external part is expressed separately does not encourage any visual connection with what is going on inside.

The difference between the House in Vail and our de sign lies in the act of traversal. In the former, the occupant or visitor must decide whether to take the stairs or the bridge. The new design proposes an architectural promenade, using both these elements as a continuous passage though the site. Robert Venturi’s so-called inclusive design method has promoted our understanding of the design and its articulation.

Through Palazzo

The Ebisu site has interesting points to concern in order to design a good Palazzo in this area. The road in front of the Ebisu site connects Shibuya; the most crowded and fashionable area in Tokyo, and Ebisu; calm and luxurious area, together. Moreover, the characteristics of the site are unique. It is long and narrow. It is also located along the Shibuya river.; the old river that has long history behind it.

With these interesting site conditions we discovered, our design approaches for the Palazzo in Ebisu are; to create relationship between users and pedestrians, and architecture together, and to create good environments for urban contexts (likes, public open spaces, gardens, etc. )

Farmstay In The City

AGRICULTURE & ACCOMODATION

INTERNATIONAL CITY, NEIGHBOURHOOD AND PRIVATE SCALE OF USE.

In this project we tried to re-incorpsed agrar- ian past of jiyugaoka into a smaller scale, In order to maintain this strong identity related to activities that habited the area from the begin- ing first through fields and farming and later through an important greenhouse activity.

To make such activities work economicaly and materially it would have to be opened to a certain amount of public, serving the global scale with accomodations, and the neighbour- hood with facilities open to local living people through a membership with an association.

This project has been conducted during the workshop held in collaboration by Tsukamo- to Yoshiharu and Andrea Matin. After the last correction, the group wished to develop fur- ther after the professors critics.

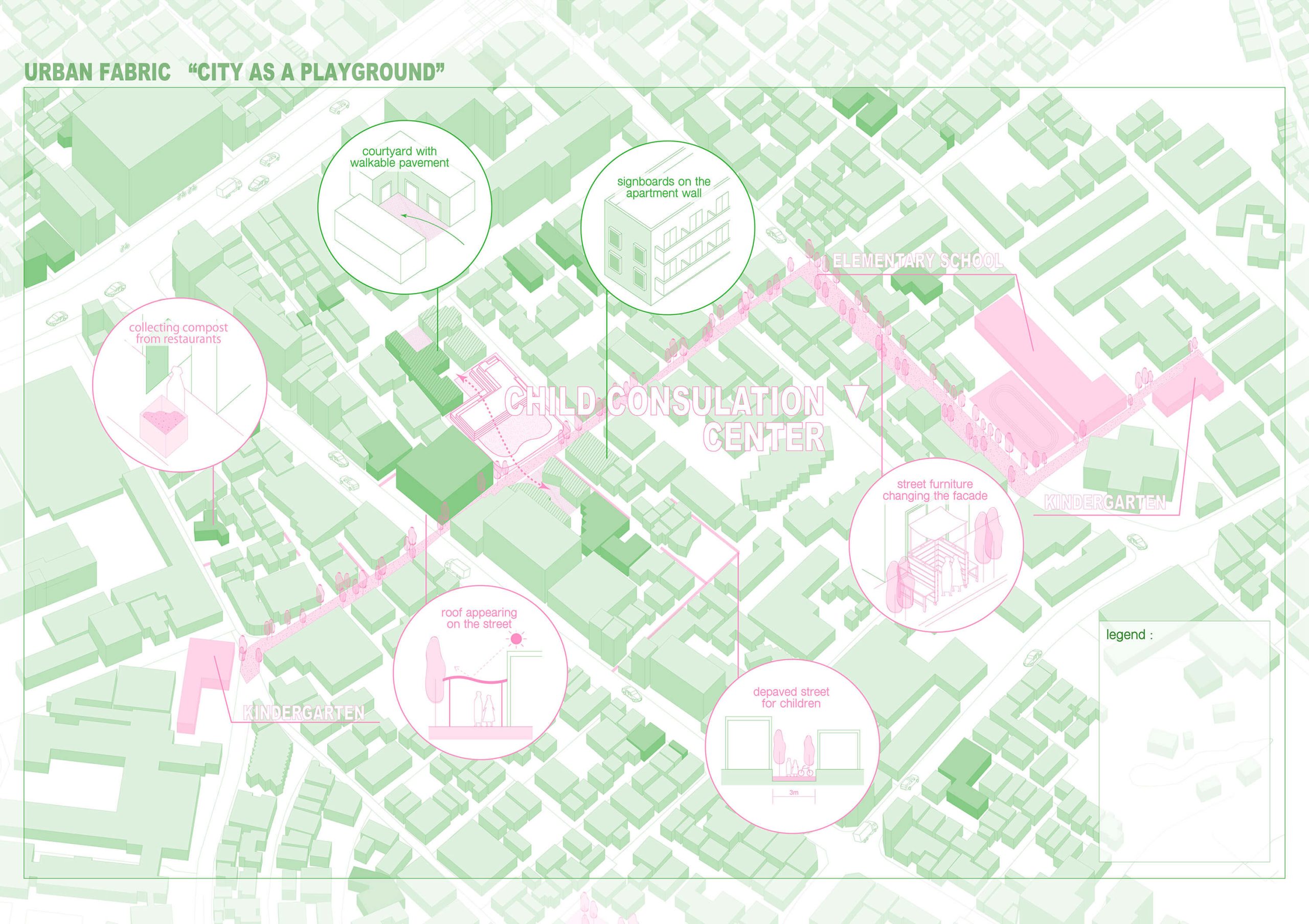

Childcare / YIMBY

Low wages, long working hours, and an increasing burden due to the excessive demands of parents cause a shortage of childcare workers. There is also the NIMBY problem, where residents’ opposition to the construction of childcare facilities has forced them into poor conditions, such as under elevated railway tracks. All of these problems are caused by the fact that childcare is regarded as someone else’s business. A binary pits child welfare against economic activity and living conditions and excludes it. We tear away the asphalt that is paved by egoism. The soil opens up childcare, which used to be on the “other side” of the wall, to the city through activities such as composting, fieldwork and, children’s play in the soil.