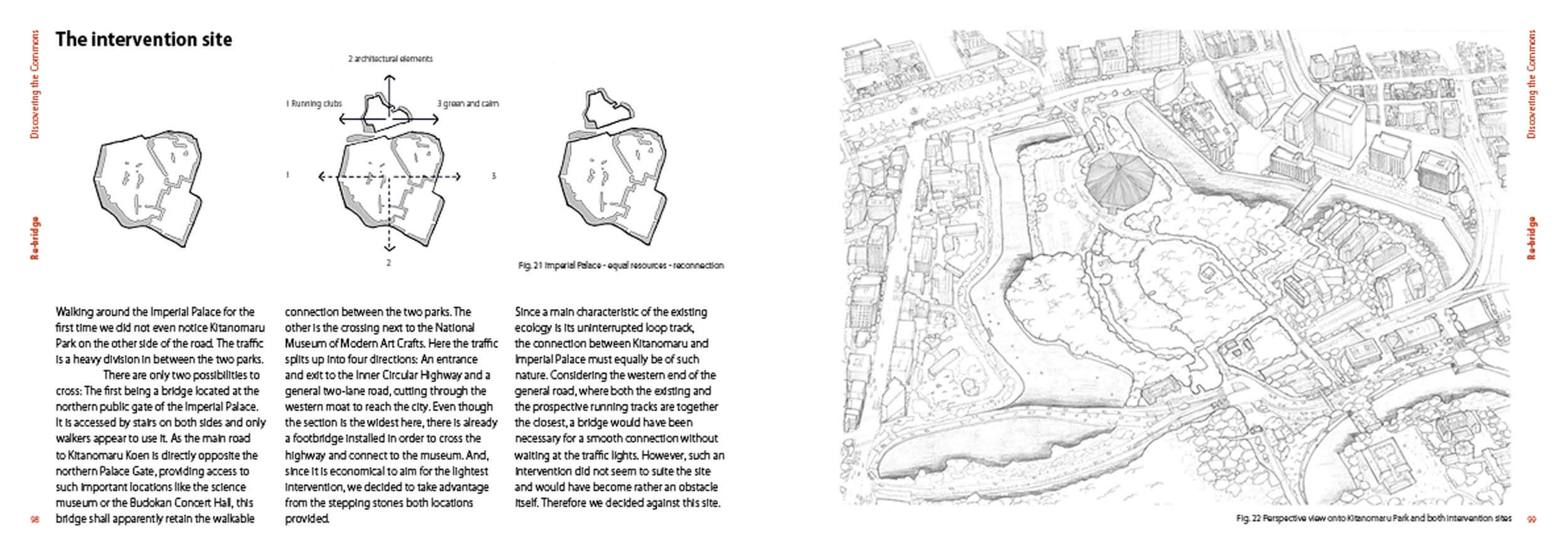

Using the power of a firmly established running praxis as a resource, our derived intervention aims at the reconnection of Imperial Palace and Kitanomaru Park “on foot”. Since Kitanomaru Park provides all the Intervention & expansion Architectural elements improving the running experience Running clubs New bridge as reconnection essentials identified around Imperial Palace, the switch for the (re-)connection of both areas is to bridge the dividing traffic at a wellsuited site. This site was found at the National Museum of Modern Art Crafts, whose situation can hereby be improved as well.

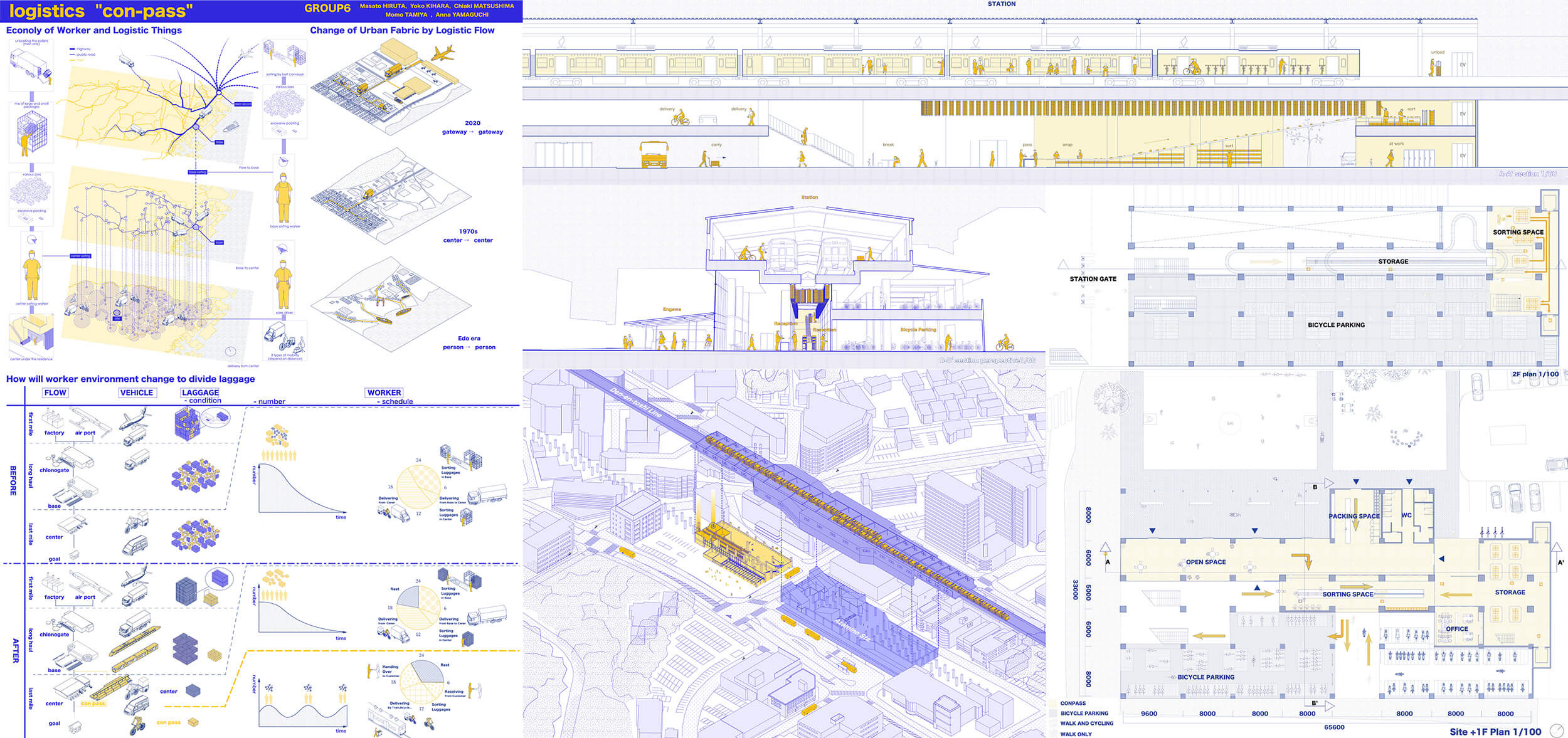

Logistics

While highly efficient logistic systems have been established in recent years, the last mile is still carried by human hands. Now that the volume of packages is increasing due to the impact of COVID-19, it is necessary to rethink the working place of essential workers in logistics.

Our proposal is a transportation system for small packages that utilize the existing train network. By utilizing the existing infrastructure and involving local users in the first and last mile, the burden on Essential Workers will be distributed.

In logistics, where more and more packages are being shipped, utilizing existing stock will become more important than building huge warehouses.

We hope this video will give you an opportunity to look back on the current situation around the essential workers.

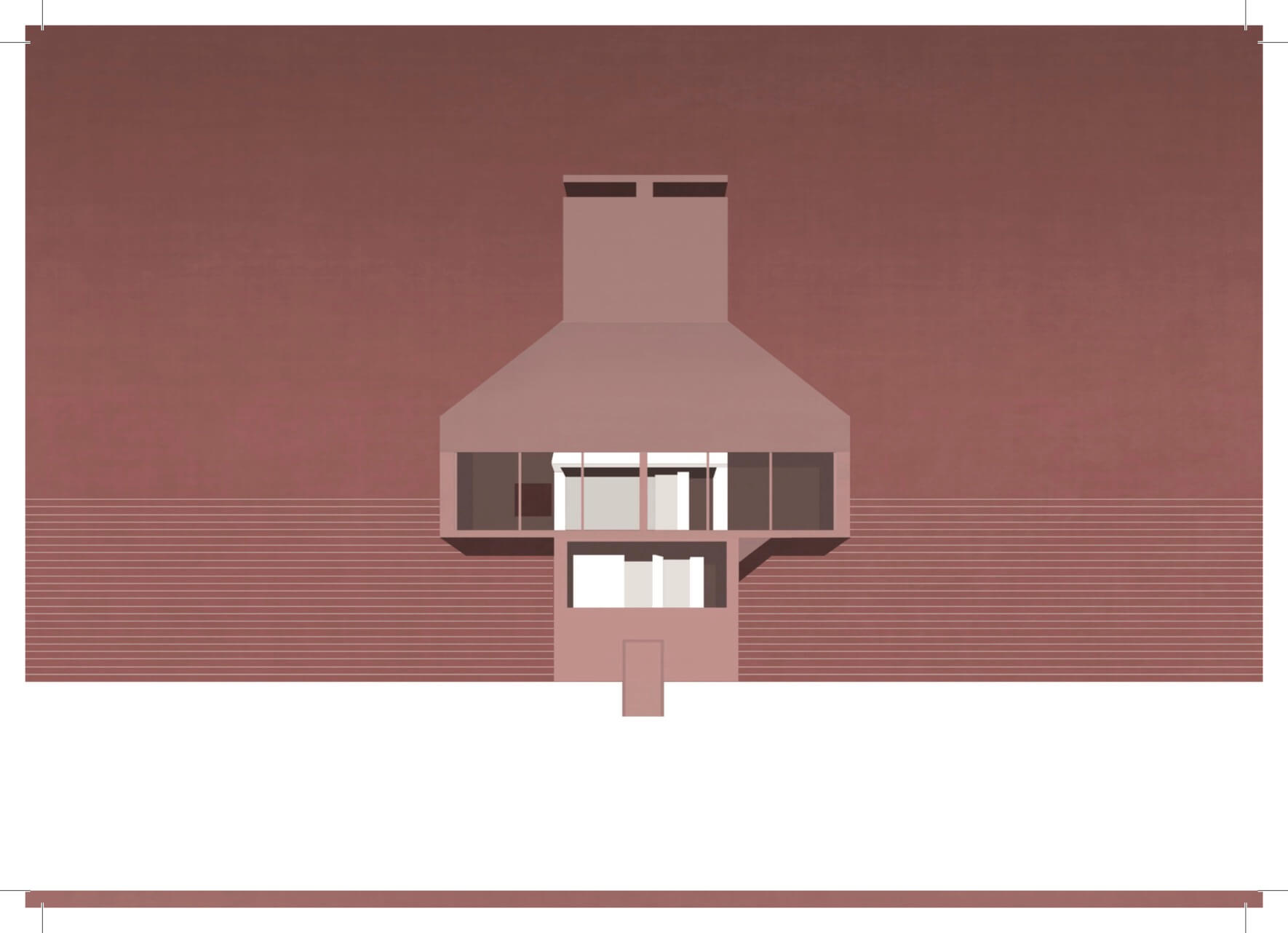

Frug House

Both the Frog House and the Gae House played important roles in shaping our design. Generally speking, these two projects can be respectively described as either a chimney with two facades or else a building with a big roof.

The main concept from the Frug House is its ambiguity, with its two facades, or faces. One on these is symmetrical and open, with large “eyes”, and the other is dug-in and shows the complex interior of the house with its various shapes and materials. Both these faces are emphasized in our perspectives. The chimney is kept because of its important position in the Frug House as well as for the design limitations and possibilities it creates. Our idea of a big roof is connected with Bow-Wow’s Gae House. Here, the roof pitch was determined by local regulations in this mostly residential area. The large-size front window makes the house more difficult to “perceive”, and this idea can be traced in both the Frug House and the Gae House.

The foursquare plan derives from the traditional Japanese “ta” character for the shape of a rice field; it consists of a simple division of the square-shaped plan into four equal quadrants. Both staircase and chimney are set in the same quadrant, forcing the stairs to dance round the chimney on the way up or down.

In our pespectives we reveal the ambiguity of our design. The symmetrical facade with its large window and hat-like roof that imitates a typical house shape dominates the first one. The second shows the playful asymmetrical backside.

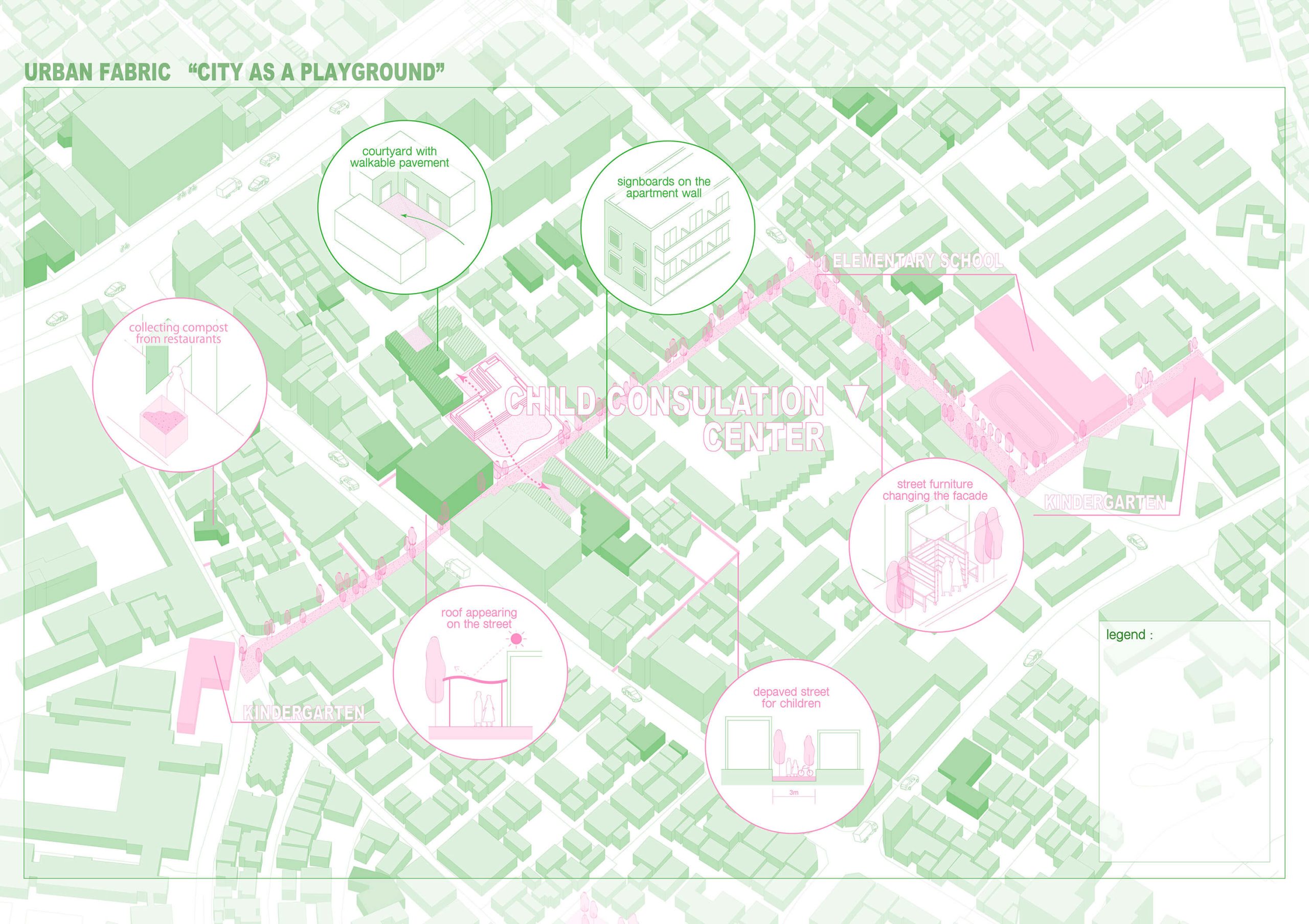

Childcare / YIMBY

Low wages, long working hours, and an increasing burden due to the excessive demands of parents cause a shortage of childcare workers. There is also the NIMBY problem, where residents’ opposition to the construction of childcare facilities has forced them into poor conditions, such as under elevated railway tracks. All of these problems are caused by the fact that childcare is regarded as someone else’s business. A binary pits child welfare against economic activity and living conditions and excludes it. We tear away the asphalt that is paved by egoism. The soil opens up childcare, which used to be on the “other side” of the wall, to the city through activities such as composting, fieldwork and, children’s play in the soil.

Sink

While the shape and function of the sink has remained largely similar throughout its modernization, as a network it has greatly changed through time, perhaps most tangibly expressed in the reduction of the visibility of water in Japanese daily life. Even though water-supply systems were introduced within cities in the Edo Period, daily water management still entailed close human interactions: guarding the water source, lifting water from the well, common laundry activities, etc. Although the widespread introduction of underground water-piping systems and pumps after World War Two enabled the direct delivery of water to individual apartments, wastewater still remained open and thus visible. Further improvements in the closing decades of the twentieth century, in the form of pressure pumps, facilitated universal direct supply, even to multistory buildings. At the same time, grey water and black water are now systematically transported to treatment plants through a sewage system, hidden from sight, before being fed back into rivers or the sea.