The research follows the transformation of the Japanese bath over the last 150 years from a set of portable objects – each designed for its respective distinct purpose yet not bound to a particular space – to a bathroom integrating the different elements into a whole unit, including the surfaces of the ceiling, the walls and the floors, as well as the hidden installations for water supply, water heating, sewage disposal, driers, lighting, and so on.

Originating as a service reserved to a privileged few – where the water was brought from the well by a servant, while another servant was responsible for heating it, preparing the bath and maintaining the right temperature – more so than with other devices and spaces in Japan, the history of the private bath is closely linked to social emancipation. In the post-war years the equipment of apartments with baths, facilitated by compact and safe gas-water-heaters, became a symbol of improvements in quality of life under the welfare state, while in more recent years the fully-equipped bath has more and more become a highly technological space of contemporary comfort and body-care, its surfaces imitating wood and tiles and thus, via associations, continuing to establish relationship to its origins, albeit an indefinite one.

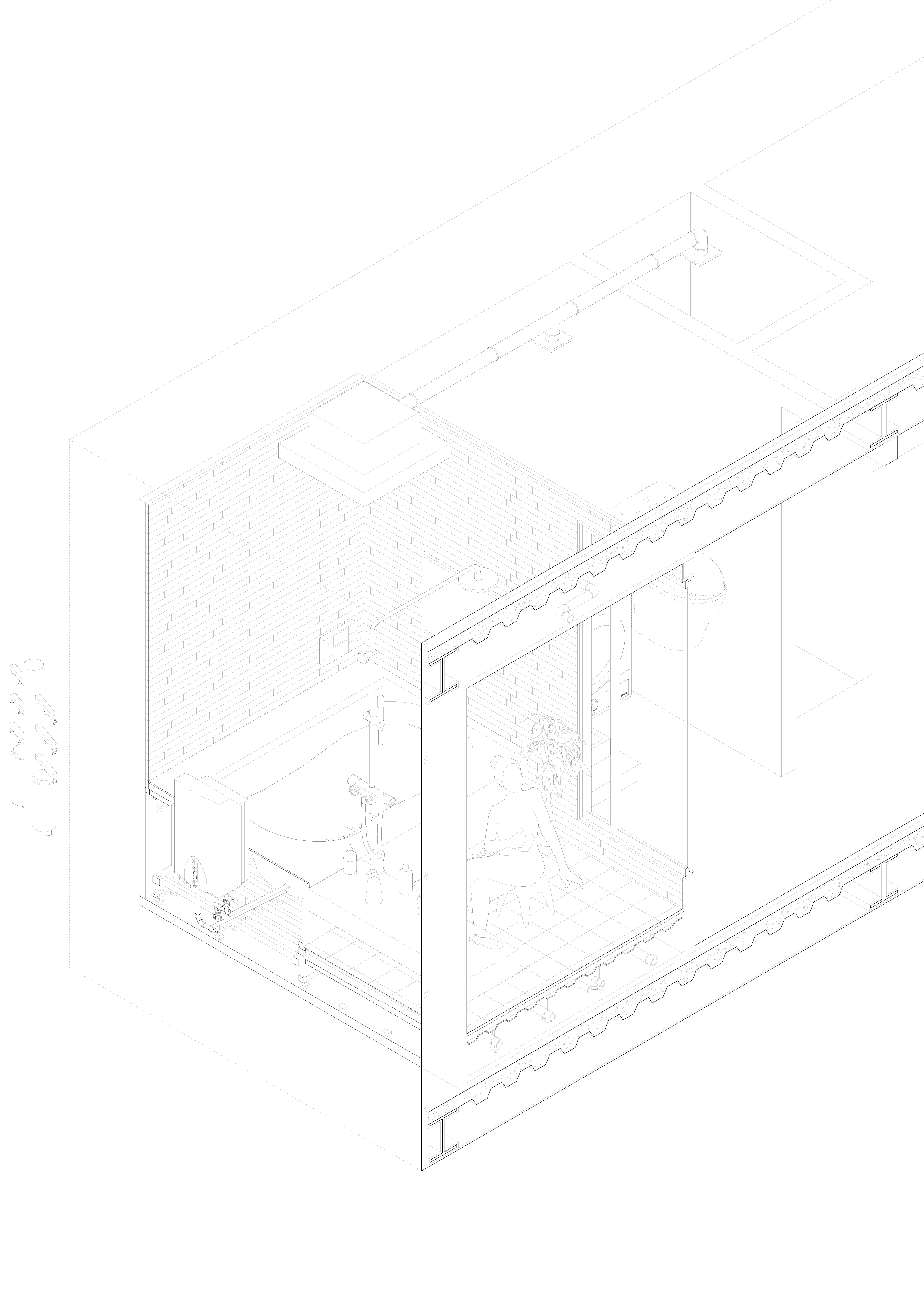

Student: Kiyoto Hiroki

Glass

Glass is a transparent material in terms of light and sight, sometimes also for sound or temperature, yet at the same time is opaque in terms of smells or the movement of persons or things. In separating different environments, it simultaneously links them; it allows interactions, yet no physical contact. These distinctive features appear to allow certain forms of human interplays to unfold that otherwise would be impossible. This is particularly true in the case of private encounters, where gestures and gazes can be exchanged through the glass; where a forbidden closeness is possible, albeit devoid of all transgression; or where even, through the reflection of the glass, silent observation is possible.